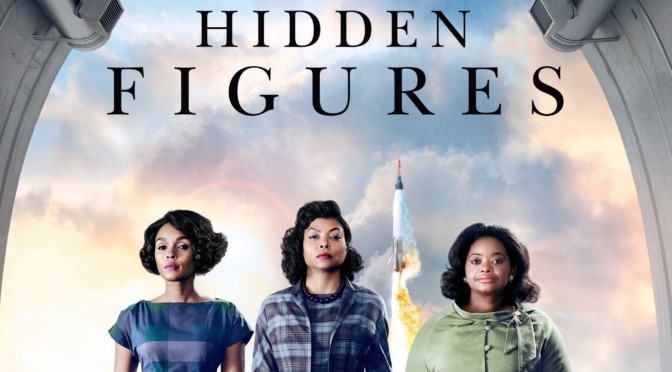

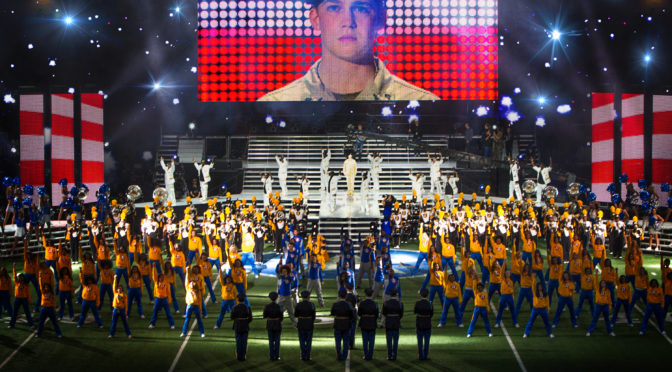

For each individual’s success there are dozens of people who helped them get there. In many cases, these people never receive credit for their efforts. Hidden Figures, is the story of how three black women contributed to NASA’s early programs. Katherine (Taraji P. Henson), Dorothy (Octavia Spencer), and Mary (Janelle Monae) are “computers” in the early 60s, meaning the perform the complex calculations needed by the engineers and scientists. Katherine has been assigned to a special task group, but has to deal with being the first black person working there. Dorothy is trying to get promoted to supervisor, a job she is already performing, but can’t win the respect of her boss. Mary wants to apply to become an engineer, but doesn’t have the required education and isn’t allowed to attend the only school that offers it. Each of the stories follow the women as they deal with prejudices against their race and their gender.

The writing is surprisingly sharp. There are plenty of witty exchanges between the women as they comment on their managers and the difficulties they have to face. Monae is particularly funny as the unfiltered, sassy member of the group. Her barely contained anger and judgmental stares lead to several amusing scenes. The film also handles quieter moments well. Katherine is courted by a charismatic military officer played by Mahershala Ali (Moonlight) and their growing romance is both sweet and comical. The screenplay adds some much needed flavor to the otherwise well-trodden narrative.

The actresses are clearly enjoying themselves in their roles. Playing technical characters is something many actors struggle with (think Mark Wahlberg in The Happening), but the cast here is believable as talented mathematicians. Spencer is sympathetic as the den mother of the group who tries to ensure jobs for her team in the face of impending obsolescence by technology. Monae’s rare moments of politeness are enjoyable as she navigates through the labyrinthine rules preventing her from reaching her desired profession. Even Henson is charming as her character’s intelligence and work ethic outshine her supposedly superior bosses. She definitely continues her signature “stink look” throughout the film, but that subsides in favor of the story.

Special note needs to be given to the soundtrack. Most period pieces rely on music of the era to help embed the audience in the past, but composers Hans Zimmer, Pharrell Williams, and Benjamin Wallfisch decided to go in the opposite direction. They use selections or original songs that are deliberately anachronistic, but instead of feeling jarring they add a modern sensibility to the film’s retro setting. This injects energy into what could have been an otherwise stuffy environment.

The real Achilles heel is that the plot is too predictable. Every potential conflict and every subsequent outcome can be guessed 30 seconds into the trailer. This isn’t a film that is trying to do something new on a story level. It’s not what happens, but who it happens to that is important. The goal of the film is to provide some much needed praise to this often overlooked demographic and celebrate the strength of women in general. That intent deserves commendation but the straightforward story diminishes the drama. There are several moments where the film attempts to create tension, but they have no real effect. We already know where the conclusion is headed and can’t get invested in the potential crises. Without that investment, the movie can only impact on a surface level. Hidden Figures is an uplifting tribute to forgotten women held back by its commonplace narrative.

3/5 stars.