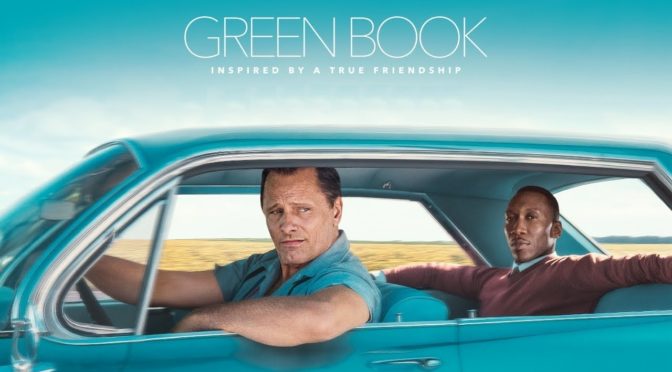

Green Book is a film that immediately raises some red flags. Being released late in the year with a well-worn setup, respected actors, and a positive message about race relations, it, on paper, reeks of Oscar bait. While some of those initial assumptions are not entirely false, the film expands beyond blatant awards pandering. The story could be viewed as a new Driving Miss Daisy with the races swapped, but it has more on its mind to say. Viggo Mortenson (A History of Violence), proving again that he is one of the few actors able to completely lose himself in his roles, plays Tony Lip, a New Yorker who gets a short-term job acting as post a driver and bodyguard for Doc (Mahershala Ali; Moonlight), a pianist, on a concert tour through the Deep South.

As characters, Tony and Doc fall into several stereotypes. Tony is a blue-collar Italian everyman. He works as a bouncer at nightclub, eats spaghetti and meatballs, and feels like he just walked off the set of Goodfellas. Doc is an ultra-posh artist with a doctorate that lives in an expensive penthouse and interviews drivers while sitting on a literal throne. Together they create the required odd couple whose relationship begins as purely professional before gradually developing into a mutual friendship as they drive further into the South and face more racism.

The early impressions quickly give way to Tony and Doc’s deeper emotions. Doc’s mannerisms are, at first, annoyingly haughty. He enunciates his language to a degree that makes him sound pompous and even hold his head titled slightly upwards as if he is too dignified for everyday people and the behavior bothers Tony until Doc’s motivations are revealed. The fact is that no matter how talented, successful, or educated Doc may be, to many of the people he meets in his travels, he is defined by his race and the racist stereotypes they believe in. This crucially recontextualizes his behavior as a defense mechanism, not a sign of arrogance.

Tony’s realization of the difficulties Doc regularly faces are expected, but the film also sheds light on some of Doc’s unique struggles. Upwards mobility is a core feature of a fair society, but Doc has to suffer the related consequences. His education and success as an artist affords him a luxurious lifestyle, but at the expense of emotional belonging. He spends his nights drinking an entire bottle of hard liquor alone in his hotel room because he no longer fits in with society’s expectations. He is, as he puts it, too white to be black and too black to be white which leaves him in a friendless state. This is an unfortunate result of social climbing that is rarely discussed in media and the film deserves praise for touching on this subject.

The biggest surprise is that the film is directed and co-written by Peter Farrelly. He and his brother Bobby are best known for creating comedies like Dumb and Dumber and There’s Something About Mary which makes Green Book a radical departure. In his first solo outing as director, Farrelly shows the restraint necessary to paint the story with a finer than expected brush. The theme of overcoming societal differences and initial prejudices is predictable, but the performances from Ali and Mortenson and the unexpected depth make Green Book an effective odd couple road trip with a commendable message.

4/5 stars.