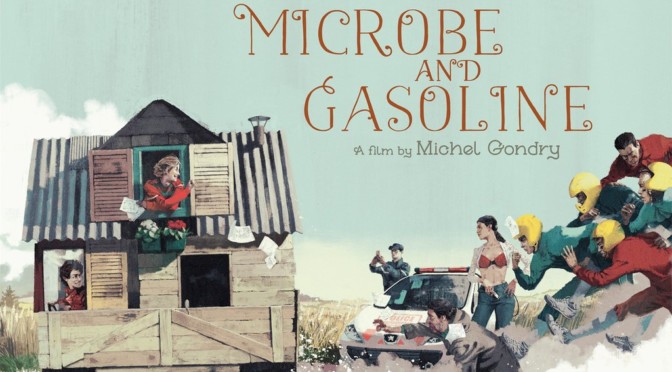

Michel Gondry (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind) is back for another tale of misfits making their way through a normative society. The titular characters feel out of place at school and at home until they meet and befriend each other. Microbe (Ange Dargent), named for his small size and often mistaken by others for a girl because of his hair, and Gasoline (Théophile Baquet; War of the Buttons), named for his scent at school after helping his dad work on cars, decide they’ve had enough of their town and that they will go away together for the summer. They start to build a lawnmower engine-powered car together only to learn they can’t to afford the required registration fees so they come up with a diversionary tactic. Design the outside of the car to look like a house and stop on the side of the road if the police show up. Houses don’t need to be registered with the DMV.

The old saying goes that it’s about the journey, not the destination. The trouble is that it takes too long for the journey to begin. Gondry spends an inordinate amount of time with the boys in school, around their classmates, and with their parents. While this is likely done to establish their need to escape from home, none of the surrounding characters are interesting. They don’t add depth to the leads and are either unsympathetic or make the boys seem unsympathetic for not listening to their parents. If anything, the early section of the film makes their departure more confusing because their families are perfectly reasonable. Instead these scenes weigh down the pacing and unnecessarily distract from the more exciting trip ahead.

When the journey finally begins, we get the Gondry experience his fans appreciate, albeit in a more muted fashion. The director is known for his makeshift arts and crafts aesthetic and that inclination is best exemplified in the car the boys build. They go to the scrapyard and pull bits and pieces of other vehicles, doors, windows, and whatever else they can find to make their escape vehicle. It is Gondry’s little touches that make this process so winning. They add shutters for their windows and even a droppable board to hide their wheels from authorities. These details showcase the director’s acute imagination, but to a lesser degree than his previous films. There are a few examples, but the film would have benefited from more of the zany contraptions, like the olfactory instruments of Mood Indigo, that he is known for.

As their car is assembled we see glimpses of Gondry’s greatest strength. His elaborate production design is the most visible aspect of his style but is actually second to the innocent spirit of his films. To anyone else, disguising a car as a house is a ridiculous idea, but to Gondry characters it is perfectly reasonable – as long as they add some flowers under the window. This sweetness was especially evident in his film Be Kind Rewind where normal people shoot their own no-budget versions of Hollywood classics, but isn’t as prevalent here. The endearing nature of two kids building their own car to get away for the summer is marred by their conflict. When the boys deceive each other it detracts from their appeal. They appear less innocent than we originally thought and it breaks the believability of their whole escapade. If they are capable of lying to even their best friend to get what they want, why would they not be able handle themselves at school or with their families? With characters that eventually lose their endearing nature and early pacing issues, Gondry’s latest effort only charms in passing.

3/5 stars.