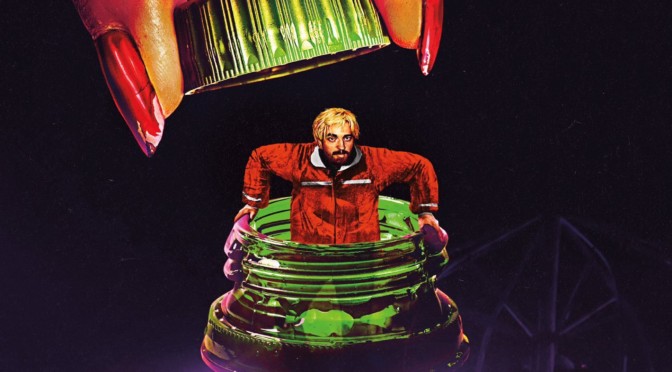

Good Time should really be called Tough Luck. Directed by brothers Ben and Josh Safdie (Heaven Knows What), the film follows two bottom-rung losers as they try to steal enough money to get away from their miserable lives. Connie (Robert Pattinson; Twilight) and his mentally challenged brother Nick (Ben Safdie) attempt to rob a local bank for $65,000. When their plan goes south, Connie decides to rescue Nick which leads to a string of progressively complicated situations as he fumbles each step along the way.

The Safdie brothers bring their realistic shooting style to the caper film. The word “gritty” is frequently thrown around to describe what appears as a more realistic shooting style, but in reality, it is a relative term. The concept is often associated with the crime films of Martin Scorsese and, in comparison to most slick, mainstream films, his works do appear more down to earth, but that is only because of the excessive sheen given to the visuals of a standard Hollywood picture. The Safdie brothers employ a style that can only be described as ultra-gritty. Their actors are mostly unknowns that look like regular people. They’re unkept and not particularly attractive. Even Pattinson, the former Twilight heartthrob, looks and acts like a lowlife and the change is refreshing. The extras and minor characters seem like regular, imperfect beings and the glamour-free appearances make Connie’s flight more intense because the setting is grounded in the real world.

The New York City of the Safdie brothers is a downright shithole. This is a part of Queens far away from the haute intellectual settings of a Woody Allen film. The movie was shot on film and features a pronounced film grain, adding a scrappy, low-budget feel to the actions onscreen. The houses we see are cramped and rundown and the few glimpses of better situations are short-lived. These are the dirty streets of the lower class, filled with people in perpetual cycles of barely making it by. The cast that populates the city is uniformly excellent with the direct, curt behavior expected from the NYC working class. Safdie as Nick is unrecognizable and utterly convincing as a mentally challenged character with his vacant, disconnected stares and delayed reactions. In their previous film, the Safdie brothers followed heroin addicts slumming their way through the city and the realism of their repeated self-harm almost became repulsive. Here, the entertaining characters and Connie’s relatable motivation prevent the aesthetic from becoming unpleasant. Instead, it lifts the stakes and clearly distinguishes the film from others in the genre.

Despite their disparate visual styles, the Safdie brothers have made their own version of a Michael Mann film, specifically Thief. They even use a pounding electric score that is reminiscent of Tangerine Dream’s work. The main difference is the caliber of their characters. Their protagonists, unlike Mann’s professional criminals, are horribly flawed. Connie is shown to have the seeds of good ideas and is crafty enough to momentarily avoid capture, but is not intelligent enough to fully solve his problems. The mistakes he makes as his outlook worsens are believable, but only for a desperate hoodlum with some awful decision-making. His narrow escapes exacerbate his situation and dig himself further into a hole which, to some, will almost be comedic in its escalation, but to others will be equally thrilling. The rough, realistic settings and increasingly precarious getaway make for a uniquely grounded heist movie.

4/5 stars.