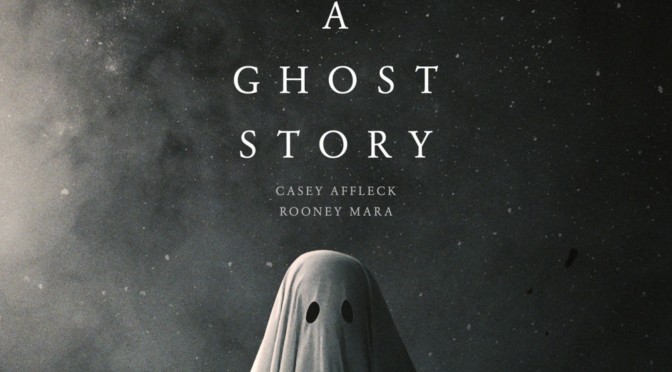

With very few words and an austere tone, A Ghost Story is going to immediately turn off some viewers. This isn’t a film with an explicit narrative, nor is it a fast one. Where others use special effects to create representations of the dead, the ghost here is almost comical in appearance. Like a lazy Halloween costume, it’s just a figure under a sheet with two eyeholes cut out. But this simplicity is intentional. Director David Lowery reteams with Casey Affleck (Manchester By the Sea) and Rooney Mara (Carol) to create a film that begins with a young couple, but focuses on a ghost left behind. Coming off Lowery’s last film, a larger-budgeted Disney-produced remake, this feels like a cleansing exercise and a return to his independent roots. Although it was well-received at this year’s Sundance Film festival, to some, it felt like an unnecessary student film experiment.

Even at a slim 90 minutes, the film may be too long. The slow, deliberate style is appropriate for the story and tone, but, despite the big ideas at play here, the film would have been improved at 60-75 minutes. The early scenes with Affleck and Mara and their gentle intimacy are compelling and the final time-spanning sequence is incredible, but, in between, the film lags. We spend too much time with the various new inhabitants of the house without progressing the story. The worst of these segments features a ham-fisted monologue from an inebriated hipster about the meaning of life in an infinite universe. This is clearly Lowery’s message to the audience, but the blunt delivery is at odds with the film’s subtle style and can be repulsive in its direct proselytizing.

Lowery is known for his lyrical style of storytelling. His first film, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, was his version of an early Terrence Malick film. Heavy on voiceovers and light on narration, it used its natural light cinematography to create a sense of nostalgia which has proved to be Lowery’s primary interest. While that film was soaked in sepia tones, A Ghost Story exists in the haze of fuzzy memory. The sets have a light fog that clouds each scene casting the entire film as something of the distant past. At one point, we meet another ghost in an unintentionally funny conversation. The other ghost is also waiting for someone, but can’t remember whom. As these ghosts wander through the lives of whomever moves into their houses, waiting for their special someone or someones to return, the film unveils itself as a look at our own emotional baggage and the legacy we leave behind. This recalls an intertitle from In the Mood for Love. “He remembers those vanished years as though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.” The ghosts misguidedly search for a feeling that they may never have again and as Lowery delves deeper into this futile search, the film expands beyond its seemingly limited scope. It becomes a film not just about one couple, but about the passing of time, memory, and the inherent history that every location carries, but rarely shows.

4/5 stars.