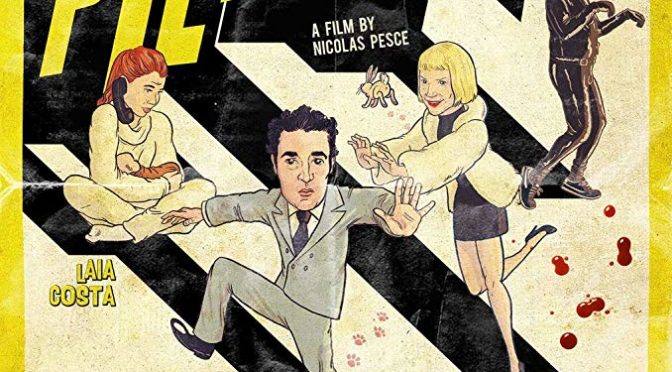

A married man with a loving wife and an adorable infant daughter has one tiny guilty pleasure: stabbing people. Coming from Nicolas Pesce (The Eyes of My Mother), the story centers on Reed (Christopher Abbott; It Comes at Night) as he plans and initiates the killing of a prostitute to satisfy his unnatural desire. The unsuspecting victim is Jackie (Mia Wasikowska; Stoker) who enters his hotel room expecting a night of S&M. The film is adapted from a novel by Ryu Murakami, author of the book that would become Takashi Miike’s Audition, so those familiar with his previous work have an idea of the kind of twisted events about to play out.

For fans of Pesce’s first film or of Murakami’s novel, the tone is going to be jarring. The source material was serious and psychological. It focused on the past of the main characters and provided deep insights into how childhood trauma and abuse can manifest in adulthood. The film is much more playful. It’s in the vein of movies like You’re Next that offer genre thrills but are self-aware of their own ridiculousness. Pesce takes Reed’s planning of the attack and turns into comedy by having him pantomime the act with a silly level of earnestness. But he doesn’t allow the humor to completely mask the actual violence. He includes unpleasant sound effects for each movement to remind us of the danger at hand. This is a movie that, while gruesome in several scenes, you are meant to have fun with and laugh at.

The film’s production design is stunning. Pesce has relocated Murakami’s story to the United States but sets it in an unknown location. He uses miniatures for the city landscape that communicate an fabricated world, one that, due to its stylization, is out of place and out of time. The technology shown indicates the story in set in the past, but the exact decade is deliberately obfuscated. Pesce uses a variety of stylistic choices to prevent the film from being grounded. The interiors have green shag carpeting and glistening wood-paneled walls that are from the 60s but the bright colors used call back to Italian giallo movies of the 70s and make the sets feel like dollhouses. The untraceable, artificial setting gives the film a strange, fable-like quality.

Pesce shows clear vision in his adaptation, but his choices often lessen the film’s impact. The film feels meticulous in its planning and execution and the subdued but unsettling acting fits perfectly with the intended tone, but the lack of psychological elements rob the story of its depth. Reed and Jackie’s histories are hinted at through well-executed but fleeting flashbacks yet this isn’t enough to add motive to their behavior. Instead, we are forced to react only to their actions onscreen, removed from the important context of their pasts that was previously present in the novel. The actions, particularly the violent ones, are well executed as Pesce knows how to make an audience squirm when he wants to, but without a grounding motivation. Piercing can be enjoyed for it rigorous details and Pesce’s laudable vison, but the lack of character development prevent the film from engaging on an emotional level.

3/5 stars.