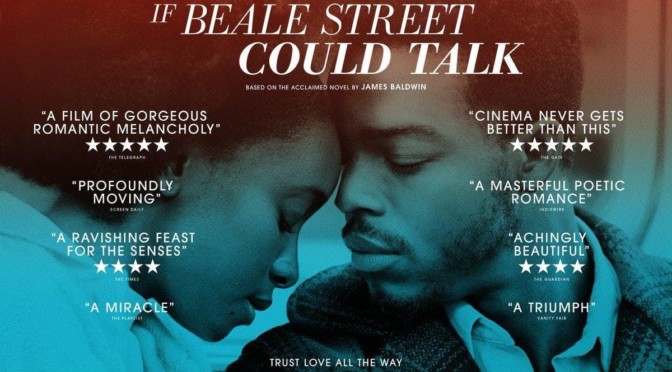

Following up a Best Picture winner is never easy, but Barry Jenkins (Moonlight) makes an admirable effort with his latest film. If Beale Street Could Talk, based on the novel of the same name by James Baldwin, follows a young couple and the difficult situation they find themselves in. Tish (KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James; Race) have known each other since they were kids. Tish works selling perfume at a department store and Fonny works a day job while sculpting wood at night. As young adults, the two fall in love and make plans to start a future together until Fonny is imprisoned for rape after which Tish realizes she is pregnant.

Visually, Jenkins makes some major strides. Moonlight was heavily influenced by the cinematography, lighting, and pace of Wong Kar-Wai (In the Mood for Love) but Jenkins steps firmly into his own style here. He still continues with the emphasis on mood and textures onscreen, but has additional flourishes. He uses overhead cameras, circling movements with heavy use of contrasting shadows, and uncommon framings. Several scenes have the character’s head centered in the frame directly facing the camera similar to a headshot. This is a composition typically rejected by filmmakers as it breaks the idea that the audience is a fly on the wall observing the plot. Jenkins instead uses it to emphasize intimacy. He reserves these scenes for dialogue that plays like personal confessions between lovers and the effect is penetrating. He places the viewer in the middle of the heated emotions, literally.

The emphasis on mood is the film’s greatest strength. Characters speak in hushed tones often through sad, aching faces and it gives scenes a disarming sincerity. This is especially true of the romance between Tish and Fonny. The tone captures the comfort and safety their bond offers and makes their struggle empathetic. Despite the potentially insurmountable odds and issues of discrimination, the film doesn’t fall into pure gloom. Fonny’s family looks to their love as a guiding force through their hardships and the use of hope rooted in love overcoming adversity tinged with the melancholy of reality strikes a subtle balance.

Yet, this subtle approach is undermined by some blunt messaging. It is revealed immediately that Fonny’s incarceration is a result of racial prejudice by the arresting police officer and systemic injustice in the criminal system. As a representation of a greater plight of so many, Tish and Fonny’s story would have been deeply affecting, but when Jenkins explicitly points out, through onscreen text, that the story represents the experience of many others, he cripples the intimacy of the story. It, along some with similarly overt dialogue, makes the film feel colder and didactic when it could have been personal and impactful on a visceral level.

The impact is also lessened by the story structure. The film makes heavy use of flashbacks and constantly cuts back to scenes of Tish and Fonny’s burgeoning relationship. The scenes themselves are fine but the editing style breaks up the flow of the film. It makes it difficult to become invested in events happening in the present when the needed background is being filled in ad hoc instead of being presented early and gradually built upon. While the visuals and general mood of the film are strong, If Beale Street Could Talk’s disjointed editing and unnecessarily blunt messaging prevent it from reaching its otherwise high potential.

3/5 stars.