Dani (Florence Pugh; Lady Macbeth) is a young woman in a rocky relationship with her boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor; Sing Street) when tragedy strikes. Her world is changed and Christian’s plan to break up with her is suspended in the midst of her suffering. Unable to say to no to her, Christian invites Dani to join him on a trip to his classmate’s hometown in Sweden to observe their traditional midsummer festival, a trip that he had initially planned without her. The celebration proves to be something far beyond what they could have ever expected.

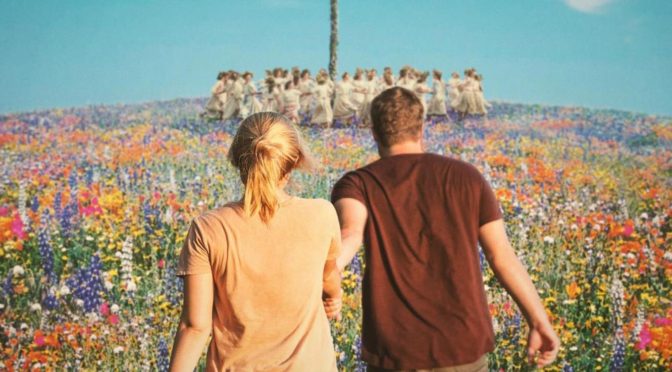

The most striking difference between Midsommar and its peers is its visuals. Horror movies, in general, take place in the dark, the shadows, or otherwise obfuscated areas relying on the potential unseen to create fear. Director Ari Aster (Hereditary) has instead created a sun-drenched, idyllic landscape. The commune is in a lush area with brightly colored buildings that, on the surface, appear welcoming. The residents happily greet their visitors, but the picturesque setting quickly begins to raise alarm. The film’s atmosphere becomes uncomfortable as things are too perfect and the bright setting appears to hide a much darker truth underneath.

Aster displays incredible talent, but doesn’t sustain it throughout the movie. There are innovative scene transitions that seamlessly move viewers from one location to the next and a great use of tension early on. The initial event that changes Dani’s life is presented so subtly that the reveal is horrifying is its simple, but grisly details. He is a director that has a knack for letting the audience know that something is wrong, even when everything appears normal. However, this effect lessens as the film progresses. Aster is able to create mystery and discomfort when the characters and settings are unfamiliar, but can’t maintain the atmosphere for the film’s runtime.

Pugh again proves herself to be an incredible actress. As Dani she is depressed, anxious, and eager to please with a growing distrust of her boyfriend and their relationship. Pugh makes Dani’s manic behavior believable and, while often irrational, she still engenders sympathy given circumstances. Her character arch is similar to Charlotte Gainsbourg’s character in Melancholia. She is initially the “crazy” one, but as their situation becomes increasingly bizarre, she seems the most at home. Her neediness and the fragile nature of her relationship with Christian deserves particular praise. Pugh’s performance captures Dani’s desperation for companionship, even with her suspicion that their relationship is nearing its end.

Like Hereditary, the film’s atmosphere isn’t able to make up for its narrative. As Midsommar continues and the true nature of the festival and the community are revealed, the film loses most of its appeal. These story beats are strange, but mostly elaborate on the nefarious nature of the cult in ways that aren’t particularly original or interesting. There some disturbing decisions made, but at that point the characters have become so far removed from reality with their acceptance of some of the shocking traditions that there is little connection or emotional impact to their outcomes. It has an incredible setting and a striking vision, but they aren’t enough to overcome Midsommar’s narrative problems.

2/5 stars.