Re-adapting a book originally published in 1966, Sofia Coppola (Lost in Translation) makes full use of her female cast. During the American Civil War, Martha (Nicole Kidman; Eyes Wide Shut) and Edwina (Kirsten Dunst; Melancholia) run a school for girls in the south. They live by themselves until one of the girls finds a wounded Northern soldier and brings him back home. Instead of immediately turning him in, they decide to help him recover first because it is “the Christian thing to do”. The soldier’s co-habitation leads to some unexpected results.

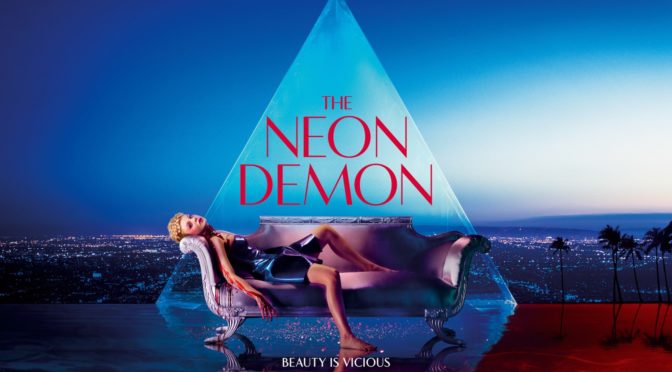

The film is unexpectedly funny. Initially, the humor feels unintentional, like the filmmaker doesn’t know that her serious attempts at drama are awkward, but Coppola’s plans soon become clear. The film isn’t just a twisted tale of what happens to a soldier brought into a house full of women. It’s about how those women, deprived of any male presence in their lives, react to his arrival. Their scrambling for his slightest acknowledgement and the way each character flaunts it over the others is incredibly comical. They each have their own unique way of trying to connect with him. Elle Fanning (The Neon Demon) as the oldest girl is the standout as she quickly switches from distrust of a Northerner to being the boldest of the group, all while trying to maintain an air of propriety.

The soldier’s impact is to immediately disrupt their priorities and their social order. Coppola expertly dissects the delicate hierarchy between the women. She is acutely aware of how women can establish and maintain their own ranks with Kidman as their alpha-female. She commands the others and they obey, that is, until a new factor is added. Suddenly, their rankings are open for renegotiation. The contrast between the adults and the girls best exemplifies this natural order. The women know their standing with each other, but it always implicit. The girls on the other hand haven’t yet learned discretion. After the soldier enters their lives, they begin competing for his attention. The women do this subtly by wearing jewelry or nicer clothing, but the girls explicitly shout “I’m his favorite!” or “He doesn’t like you”. They know that his affection has become the new determining factor of power within their household. His presence rattles their standings and puts the house into temporary disarray when Martha can no longer wield the power she is used to.

The film then turns this power dynamic on its head again. Having examined the ways in which women can be divided, Coppola pushes into how they can unite. After more changes occur, the hierarchy is again reshuffled with the women no longer competing against each other. What they are capable of and, more importantly, the proper manner in which they handle it is hilarious. Coppola embeds the film’s narrative turns in the etiquette of the time making even heinous actions appear somehow polite and, for a lack of a better term, “lady-like”. The Beguiled is a smart, feminist take on intra-sex rivalry wrapped in the tropes of a twisted thriller.

4/5 stars.