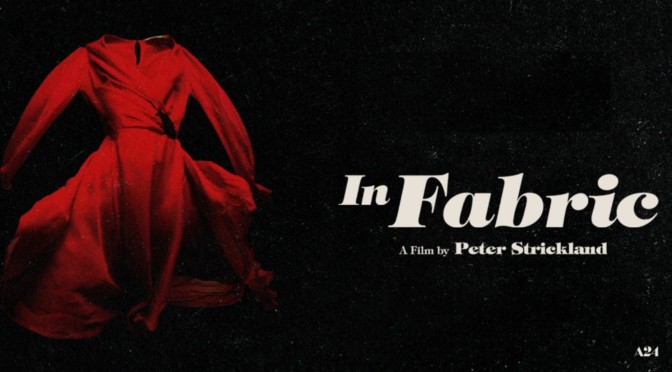

In Fabric is the story of a killer dress – literally. Somewhere in England, Sheila Woodchapel (Marianne Jean-Baptiste; Without a Trace), a divorced mom, eyes a striking red dress on sale at a local department store and, after speaking with the strange staff, she decides to buy it for an upcoming date. Later in the film, the dress is worn by a soon-to-be-married appliance mechanic named Reg Speaks (Leo Bill; 28 Days Later) as a joke for his bachelor party. In both cases the dress interferes with their sanity and has a devastating impact on their lives.

Director Peter Strickland (Berberian Sound Studio) attempts an eerie tone that doesn’t culminate in anything. The film’s style is a mix of giallo and David Lynch that seems intriguing at first. The visuals, the film’s strongest component, are filled with the searing reds and greens from the giallo genre and the acting would easily fit into most of Lynch’s films. The department store workers speak as if from another reality with flowery, verbose descriptions of clothing and an unnatural cadence. They, with their powdery white makeup, are practically an entire team of lesser Mystery Men from Lost Highway. Their dialect implies some ulterior motive, but what that motive is or how it relates to the Sheila or Reg is never explained or made meaningful. It’s hinted that it may be the dress itself, somehow sentient, that is behind the tormenting of its wearers, but its purpose is also unexplored.

The first half, focused on Sheila, is by far the stronger story. Jean-Baptiste is sympathetic as a mom providing for her adult son, but also lonely after her divorce and her simple goal of looking sharp and meeting someone is very relatable. She works as a bank teller and reports to a pair of middle managers that appear to be Strickland’s attempt at satire of convoluted corporate procedures. These two repeatedly call in Sheila for minor transgressions, like the use an informal greeting, and have an interesting dynamic as they finish each other’s sentences but feel like they were pulled out of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil rather than this film. After the narrative changes protagonists, it loses most of the minor interest it had created. When Reg enters the film, he encounters many of the same issues Sheila had with the dress in the same exact way. His section adds little to what has been shown as the film essentially repeats itself with the dress targeting a new victim.

Films can be obtuse and open-ended, but In Fabric fails to create and maintain emotional investment. At times, it appears to be a horror movie about a cursed garment, but the changing characters and lack of background prevent the viewer from being engaged with the horror. There isn’t a human slasher villain, only a literal piece of cloth. This is a gigantic hurdle for Strickland to overcome to create any fear in the audience and he, unfortunately, is unable to. There seem to be moments of satire aimed at consumerism, characters constantly talk about sales, or potentially materialism, the store staff is aroused by their mannequins, but these are at the periphery. Its vivid colors and attempts at a surreal tone are not enough to compensate for In Fabric’s lack of emotional connection and tension in its horror premise.

2/5 stars.