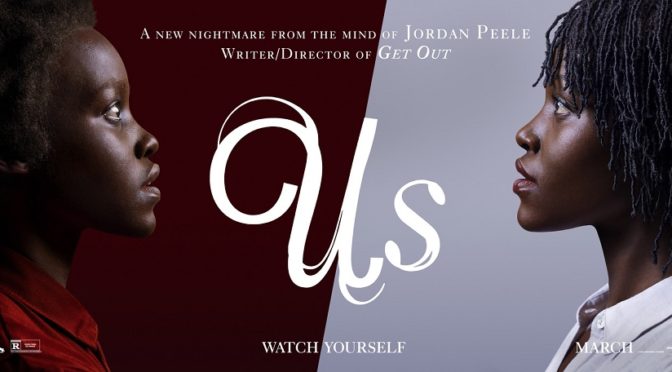

Us is the story of a vacationing family that is visited by unwanted guests. Lupita Nyong’o (12 Years a Slave) and Winston Duke (Black Panther) play the Wilsons, a couple with two children going on a trip to their beach house in Northern California. One night, four masked strangers stand in front of their home. The people closely resemble each of the Wilsons and begin a murderous rampage as they attempt to kill their doubles. These intruders are known as the Tethered and the Wilsons have to escape and find out who these strange people are and why there are being attacked. The film is the second title from comedian-turned-director Jordan Peele (Get Out) and another entry into his particular brand of horror.

Peele tones down the social commentary in Us. His previous topic of race relations is barely touched upon and instead he focuses on wealth inequality. The demented doppelgangers are the have-nots to the main family’s haves and the disparity between their upbringings is mentioned in a monologue, but it never becomes the central theme.

For most of its runtime, Us is a slasher film. The initial encounter with the shadows is a great moment of tension. Peele weaves his camera through the hallways as the family frantically closes open windows and the other family invades with an relentless dedication reminiscent of a Terminator. Peele is not able to sustain this level of tension throughout the film. After the villains have been introduced and have explained their backgrounds, they lose their mystery and with it their menace. They still pose a clear physical threat to the main cast, but no longer have the fear of the unknown to accentuate their actions.

Horror films are rarely known for their logic, but Peele still makes an unsuccessful attempt. During an initial confrontation, the Tethered explain who they are and why they are hunting down the main cast. This proves to be a fatal mistake as the explanation raises several questions that reveal plot holes. Typically, it’s best not to think too critically about the mechanics of a horror villain, as was the case with Get Out, but Peele forces these issues into the limelight. As is the case with most horror films, the Tethered’s origins may have been more effective if only suggested rather than explicitly told.

Without consistent tension or an interesting social angle, Us is a step-down from Get Out. Get Out also had issues maintaining tension, but the commentary on racial prejudices provided enough substance to compensate. Peele is still a talented filmmaker though. He elegantly foreshadows later plot elements, even providing an early hint at the Tethered’s origins for genre film fans, and gets great performances out of actors. Nyong’o and the children are standouts playing both their regular selves and the Tethered. Duke, as the goofy dad, isn’t at the same level but does provide a good source of humor. Peele has the rare talent of being able to weave humor into a horror film without feeling unnatural and it continues to be his greatest strength has a director. Us doesn’t have the tension or narrative foundation needed to thrill, but Peele’s talents provide do some bright spots.

3/5 stars.