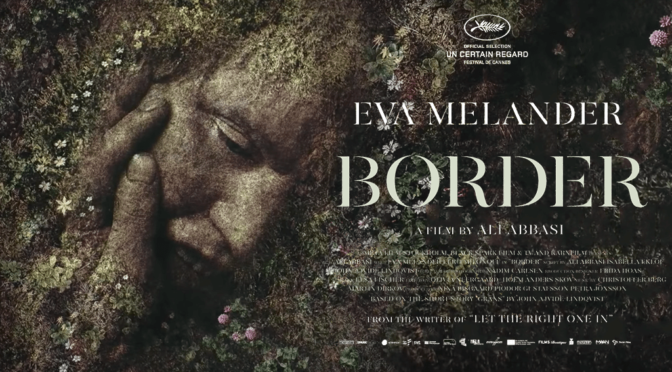

A peculiar looking woman named Tina (Eva Melander) works as border security in Sweden. She possesses a preternatural sense of smell that allows her to literally sniff out smugglers. She doesn’t just smell food or drinks they might be hiding, she can smell guilt. She lives in a small house in the woods with a man that isn’t her significant other, but also not quite just a roommate either. One day she smells something wrong with a man, Vore (Eero Milonoff), who seems to share her physical features. Eventually she befriends him and offers to let him stay in her guest house. The film is based off a short story by John Ajvide Lindqvist who also wrote the novel Let the Right One In which was later adapted into two successful films. With these two films, Lindqvist has demonstrated his interest in loners and fairy tales. Let the Right One In had an isolated child bonding with a centuries old vampire and in Border we have a woman dismissed for her appearance who discovers that she is a troll – literally.

Initially, Tina’s sense of smell is intriguing. She seems like she might become some type of unconventional superhero a la Unbreakable. A subplot of this story does explore this idea as Tina assists law enforcement with a difficult case and it becomes the most interesting part of the movie. She is shown to be a kind person, despite how she is often treated, and would be an investigator worth rooting for in a crime story. But this is not that kind of film.

Director Ali Abbasi (Shelley) uses Tina’s appearance to examine an outsider’s perspective. Tina has spent her life believing that she was an ugly person, disregarded by society and loved by only her father. In early scenes, Abbasi frames Tina by herself, gazing into the distance. He quickly establishes her isolation, but too much of the film is spent on these and other slow scenes of little value. It isn’t until Vore enters the picture that Tina realizes she is of another species. Vore explains that everything that made her different, her looks, her sense of smell, and the long scar on her lower back are related to her being a troll raised as a human. This revelation frees her from the negative labels she had absorbed. Her response to being nonhuman is contrasted to Vore’s. Tina hasn’t been treated well, but she harbors no ill will towards others while Vore has a militant pro-troll mindset. Through them we see how people can react to rejection and mistreatment and how these experiences can bind similarly outcast individuals.

Their shared trollhood eventually grows into a romance that, while believable, doesn’t have chemistry. It is touching to see Tina’s behavior change as she feels belonging for the first time, but the actual attraction between her and Vore has problems. Vore has a suspicious, almost predatory edge to him that makes even his kind praises seem dubious, but her attraction to him seems like a foregone conclusion. He is the only other troll so naturally they get together. Abbasi spends a significant amount of time on their relationship, but it, like the film in general, doesn’t have a payoff. The slow pacing and subdued acting make the film drag on until its unsatisfying conclusion. We’re left wondering why all the strangeness and deliberately unconventional plot details were even necessary when the final outcome is nothing special.

2/5 stars.