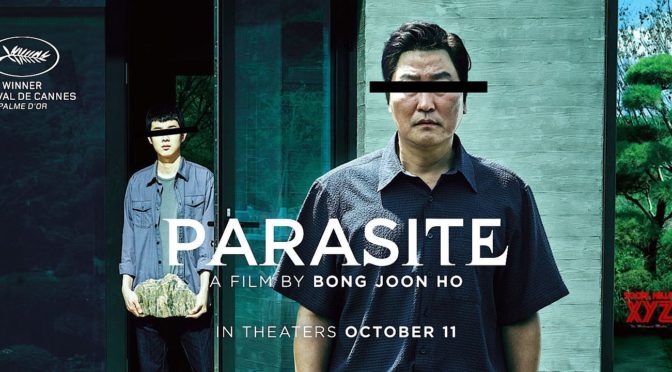

With his first film to be made fully in Korea in a decade, director Bong Joon-ho has created his best work since Memories of Murder. Parasite is the story of a poor family living in a basement apartment . The father (Song Kang-ho) was a driver but, like the rest of his family, is unemployed and barely scraping by. The son gets an offer from his friend to substitute as an English tutor for a rich girl, despite his lack of a college education, and enters into a completely different world. Using the English name “Kevin”, he meets the Parks, an affluent family that pays him a sum that is inconsequential to them, but life-changing for him.

The film begins as a comedic con movie. Kevin (Choi Woo-sik; Okja) tricks his way into the wealthy household on his friend’s recommendation, but the film becomes increasingly ridiculous as he, and each subsequent member of his family, devise ways to get their loved ones a job, even if that job is already taken. They set up elaborate schemes to put the existing staff out of work that, while unfair to the innocent employees, are hilarious in their audacity. The rich mom appears kind, but gullible, or “simple” as Kevin’s friend puts it, and falls for their innocuous line of recommendations. Slowly, the entire Kim family becomes employed by the Park family and their clumsy attempts to hide their relationships become a great comedy of errors.

Without spoiling anything, their deception escalates with unforeseen consequences. This is where the plot thickens and the film’s themes begin to show themselves. While the Parks seem kind and welcoming at first, the disparity between their lives and the lives of the Kim family comes into focus. During a heavy rainfall, the Park family, in their walled off home above the city streets, are largely unaffected, with their son even camping outside during the storm. The Kims however live in a partially underground apartment. The rain leads to their home being flooded to chest-high levels of sewage water, drastically impacting their lives in a way the Parks are not even aware of. In the subtle way they treat their employees, the Parks show their aversion towards the Kims and their lower class life, gradually changing how the Kims, and the audience, view them. The Parks may be the victim of deception, but their attitudes create a moral gray area.

Bong is known for his skillful blending of genres and tones, but Parasite is remarkable even by his high standards. The film works on so many levels. It’s a thriller, a farcical comedy, and a commentary on class, all without conflicting tones or sacrificing the strength of one genre for the other. As the film dives into unexpected territories, it feel completely controlled and reaches surprising levels of emotional significance. Bong uses the film to comment on class privilege, but also the sacrifices and glass ceilings of the lower classes. He shows what the poor must struggle through, what they dream of, and what their realities are without completely absolving them of blame. He isn’t afraid of showing multiple perspectives. Parasite is masterful blend of genres and a tonal juggling act featuring a complex look at wealth disparity in modern society.

5/5 stars.