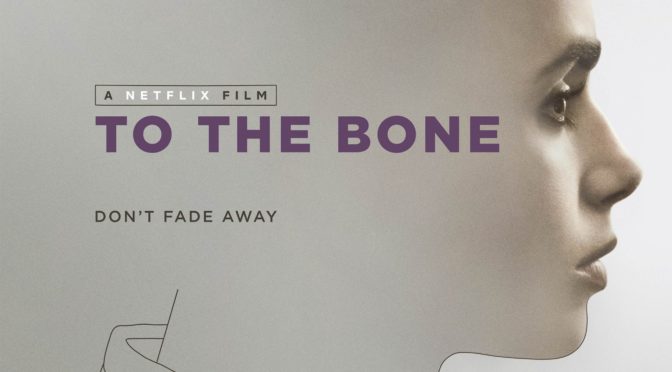

[BS Note: This film is currently available for streaming on Netflix]

With glamorous images of people with seemingly perfect looks and illustrious lives exacerbated by social media, we are inundated with unrealistic ideals of how we should look and behave. For some, this can lead to harmful behaviors, namely eating disorders. To the Bone follows Ellen (Lily Collins; Mirror Mirror), a 20-year-old living with anorexia nervosa. She has just left her fourth treatment facility without showing any improvement and returns home to a stepmother who is unsure of what to do next. She finds one final physician who may be Ellen’s last chance at recovery.

Keanu Reeves (John Wick) turns up in an unexpected, but welcome supporting role. He plays Dr. Beckham, an eating disorder specialist known for his high success rate and unusual methods. Reeves plays Beckham as a tough, no-nonsense doctor. Instead of sterile clinical language, he is direct and almost confrontational. “I’m not going to treat you if you aren’t interested in living”, he tells Ellen. His experience makes him impatient with pleasantries, but detailed during actual treatment and his advice, however blunt, is filled with support. He genuinely cares for the well-being of his patients and Reeves’s confident performance highlights his intelligence, understanding, and compassion.

Director Marti Noxon’s approach to group dynamics goes far beyond the typical addiction movie. Instead of only focusing on Ellen’s struggles, she takes time to explore the damage done to her loved ones. This ranges from a mother too hurt to look at her suffering daughter, a frustrated stepmother, an absent father, and a loving younger sibling who misses having her older sister in her life. Noxon understands that these afflictions also manifest differently. She uses the different patients in the treatment home to show the lengths to which people will go. Whether it’s laxatives, diet pills, or hiding bags full of vomit, these are people trapped by their disorder into an unstable frame of mind. As a test of her size, Ellen tries to wrap her thumb and forefinger around her bicep. The film is deeply disturbing in its depiction of the unrealistic, self-destructive ideals the patients impose on themselves and the rippling effects they have on their families.

Collins is frightening in her performance. She has written about her own struggles with eating disorders and she clearly draws from those personal experiences in her acting. Her progressively skeletal frame and gaunt facial features show her deteriorating condition. “You’re a ghost”, her mom says after seeing her. The film has faced some backlash over its depiction of anorexia, but it neither glorifies nor indicts people with eating disorders. It repeatedly states its position: that this an addiction and one without clean answers. When Ellen’s stepmother tries to tell her doctor that the disorder has something to do with her mother, he cuts her off and says, “It’s never that simple.” This isn’t a film about easy solutions or motivational speeches. Noxon delves into the obsessive behaviors of anorexics and the fractured families that may be both a source and symptom of the disorder. The only exception is a dream sequence near the conclusion that is embarrassing in its literalism and contradicts the film’s grounded tone. Save for this specific mistake, Noxon has created a realistic examination of the struggles of someone clinging to warped body image ideals and the turmoil it can create for those who love them.

4/5 stars.