[BS Note: There are two versions of Voyage of Time: a 40 minute documentary and a 90 minute feature length version. This review covers the former.]

Almost 40 years ago Terrence Malick had a dream. He wanted to make a movie that explored the origins of life. The movie, then tentatively titled Q, was going to be backed by Paramount until Malick left and went on his famous 20 year separation from Hollywood. Apparently, he never stopped working on the idea. Parts of the project were used in the origins sequence of The Tree of Life and since then an effects team has been at work on what is now Voyage of Time. Clearly intended for IMAX screens, Malick has created a documentary unlike any other.

His goals are less didactic than philosophical. Malick, who graduated with a degree in philosophy from Harvard, has never been interested in literal facts. Instead, he uses voiceovers by Brad Pitt to ponder the meaning of life. While existential quandaries are par for the course in anything Malick has done recently, the thoughts here are much more broad than usual. These are questions that apply to life in general rather than the particular experience of a character. Many will view this narration as pretentious and navel-gazing and they would be mostly correct. The opening epigraph addresses the audience with “Dear Child”, making the spiritual tone apparent from the beginning. There are moments of profundity scattered within the voiceovers, but they lack the impact they had in The Tree of Life. If anything, this film proves that Malick’s brand of exposition requires a human story. It grounds his thoughts and provides a context for the audience to connect with.

Regardless of their varying quality, the voiceovers are largely forgotten. The visuals overwhelm and envelop all expository aspects of the film. The footage was shot with the format in mind and watching it on a 90 foot screen is nothing short of awe inspiring. The visuals swallow the audience whole. Combined with the sound effects, namely the rushing of water and classical music, they form a gestalt that renders any attempts at exposition inconsequential.

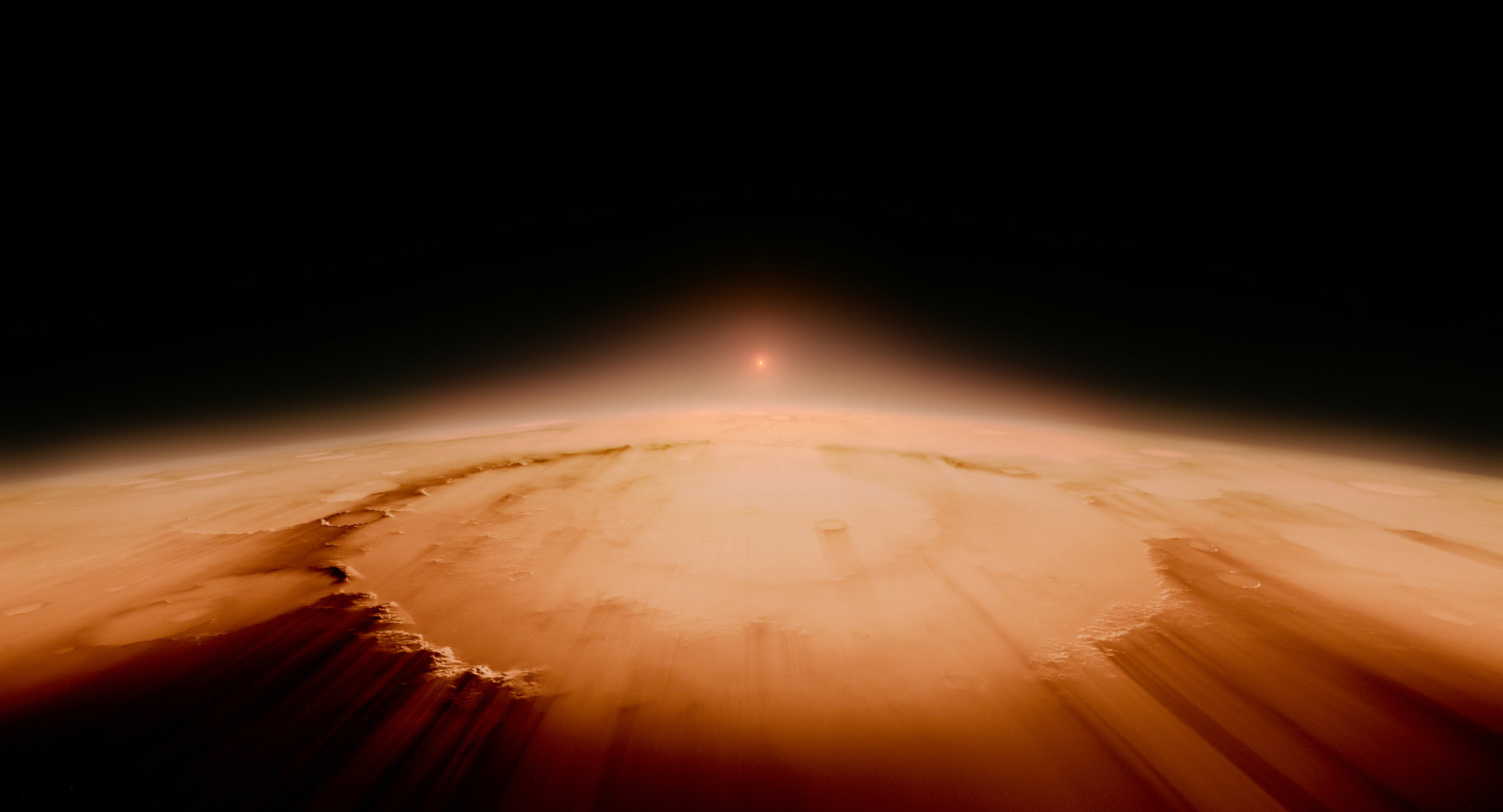

It’s unclear how much time and money was spent creating the special effects, but whatever the cost was the final product is worth it. The scenes depicting the formation of the universe and showing celestial bodies are particularly enthralling. They use chemicals, coloring agents, and models to create practical effects that are timeless. Seven years ago audiences were amazed by the visuals in Avatar, but computer generated models always show their age. Soon, the effects in Avatar will look dated but in another 50 years, the cosmic scenes here will still be stunning. The only complaint is that there are not enough of these universe creation scenes.

The film’s narrative is mostly empty. Pitt’s voiceovers aside, the only real story available is knowing that each scene moves forward in time. Some may not find this enough to carry a film, but at 40 minutes the lack of story is not an issue. After the creation sequence, Malick interweaves scenes of nature with footage of a young child playing in the grass asking the question (literally) “How did we get to who we are?” The question is never answered, but rather discussed. While coming to a Terrence Malick movie expecting anything to be explicit is a mistake, many will still find the lack of resolution, and therefore the film itself, pointless. For those wiling to embrace Malick’s elliptical style, Voyage of Time presents the divine beauty of life with standard-setting visual effects.

4/5 stars.