At the end of last year, 2016 looked like it would be the year of the video game adaptation. Beloved franchises from PC to mobile to console were being brought to the big screen in ways that seemed like they could actually work. This year we have Angry Birds, Ratchet & Clank, Warcraft, and Assassin’s Creed. The first two are animated films, Warcraft is live action with significant motion capture, and AC is live action. Before we discuss this year’s lineup in detail, let’s revisit the history and background of these films.

Video game movies are bad. That’s not an opinion, until now it’s been an accepted fact. The track record of video game adaptations has become a running joke to the point that fans of either medium groan whenever news breaks that a franchise has been optioned. In theory, it shouldn’t be abnormal for a video game movie to be good. Games have great, imaginative settings and, like blockbuster movies, they’re often driven by spectacle. The problem behind this sub-genre can be answered with two simple questions: “Why?” and “Who?”.

Whenever a work is optioned, it is usually done for either love of the source material or potential for financial returns. In the case of video games, it has mostly been the latter. Instead of viewing a game as an individual piece of content, producers and executives have been making video game adaptations based on the built-in fan base. Everyone played Super Mario Bros. growing up so why not make a movie? If even a small percentage of people who played the video game buy a ticket, the movie will profit. But what they’re not thinking about is what makes these games popular. People don’t play Mario because they love bipedal mushrooms or a giant turtle-dragon thing. They’re fans because of the interactive element and how it makes them feel. In Mario, it’s the tension created by barely landing on a platform, but this doesn’t translate at all to a film. You can’t adapt gameplay.

Instead, producers use their regular toolkits. They take successful video games with outlandish premises and try to shoehorn in a generic script. Was there anything about the Need for Speed movie that reflected the actual game? No. It was a heist movie made because The Fast & the Furious is popular and Need for Speed is a recognizable brand. It didn’t matter that the franchise had almost no storyline or greater world development, because financiers were only looking at the large box office potential given the sales of the video games and the success of similar films. They took the existing name and forced in a basic plot so bland that no fan would have been able to guess that it was an adaptation without being told.

Video games don’t easily conform to standard storylines. This is true on multiple levels. On one hand, video games can be long. A retail game can sustain between 8 and 100 hours of playtime, depending on the title. Telling a story across this kind of timeframe not only allows for more plot points, but gives the player a chance to live in the setting and understand the characters in a way no regular film can. After spending 40+ hours playing Mass Effect 2, the side character Mordin Solus wasn’t just a character I liked, he was my friend. The mere constraints of the medium prevent single films from forging these kinds of relationships between the audience and the characters or settings.

Video games are not only story-based. If someone were to recommend a book and say “Just ignore the story” that would be a ridiculous suggestion. Unlike books, video games aren’t solely defined by their writing and unlike films, they have an additional layer beyond their visuals. The key to video games is interactivity. There is a tension created by the collision of prewritten narrative and player agency. As a character grows, the player is not just a viewer of the change but an active participant. They feel ownership over the events that have taken place.

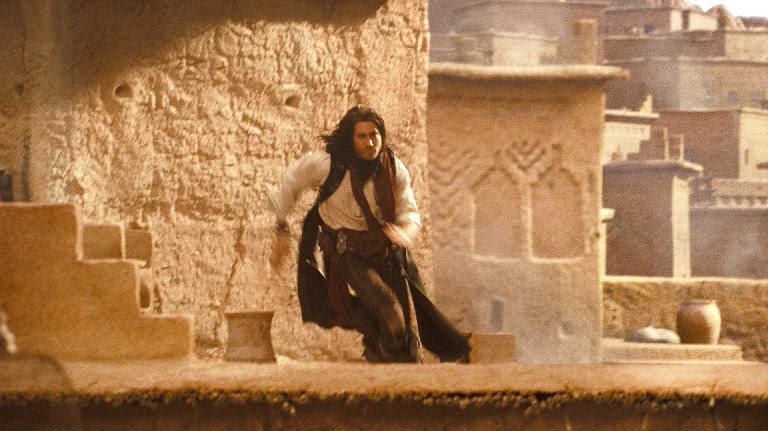

It is the interactive element of video games that those adapting them to film most often miss. Anyone adapting a video game needs to look beyond the surface level a franchise’s features. Yes, the Prince of Persia series’s signature move is wallrunning, but shots of Jake Gyllenhaal scampering along a wall won’t have the same impact. It’s not just what a character does in a video game that matters, it’s how it makes the player feel. Wallrunning is about agility, power, and resourcefulness. You, the player, were able to outwit the precarious architecture and the feeling that results is one of nervous relief, satisfaction, and pride. These adaptations need to target the core feelings produced by playing, not watching, the video game.

Much of the issue stems from the types of people making these films. As stated earlier, there are some that look at a video game and only see the guaranteed fanbase, but there are also issues of familiarity, both with the particular franchise and with video games as a medium. A successful director would need to understand filmmaking techniques as well as the language of video games. In most adaptations so far this hasn’t been the case. Often times the director has failed on both accounts, neither being an accomplished filmmaker, nor having any understanding of video games.

The best examples of how to make a successful adaptation come from a different medium – comic books. Pre-2000s there were many comic book film adaptations that were unsuccessful. This happened for very similar reasons to video game adaptations. The people making the films did not have the understanding needed of both mediums. It wasn’t until this century that the comic book era we currently live in began. Unlike previous films, these were being directed by talented filmmakers who grew up with comic books giving them a deep understanding of the medium and how it was both similar to and different from film. Video games have not been around nearly as long as comic books. If we want to start counting with the Nintendo Entertainment System, it’s only been a bit over 30 years. Most higher ups in the film industry tend to be over 50, so the people in charge now likely didn’t grow up with the medium. They’re trying to understand something foreign to them and fumbling the adaptation in the process.

However, soon the kids that grew up on Zelda and Final Fantasy will be in charge of directing or producing feature films. Once that happens, I expect the abysmal results of video game adaptations to improve significantly. Will there be a Nintendo Cinematic Universe? Probably not, but as video games diversify and grow there are more franchises that are ripe for optioning and more people qualified to take full advantage of them. Each of this year’s adaptations showed promise. Angry Birds lacks any story as a video game, but as an animated feature, it wasn’t a hard sell to think that someone would be able to tell a decent story using those characters. The Ratchet & Clank franchise on the other hand has always felt like a playable animated movie so the adaptation seemed completely natural. Unfortunately, the film was unable to capture the charm of the games and by all accounts was generic and forgettable.

Warcraft represented the best chance at a good, perhaps great film. The lore of the franchise had been developed for over a decade and was expansive with many individual plotlines that would function well in a film. That combined with the rising star director, Duncan Jones (Moon, Source Code), should have created unprecedented enthusiasm, but it didn’t. Despite Jones’s filmography, the consensus prior to release never rose above cautious optimism. When it finally debuted after a long post-production, Warcraft was panned by most critics and bombed at the US box office (although it did well in China). In reality, it was an enjoyable, but flawed film. Jones is a fan of the video games and was able to bring the appeal of the large-scale battles. Sadly, the overall quality was undercut by the burden of establishing a Warcraft film franchise. It wasn’t a giant leap forward, but did move in the right direction.

The next shot at true vindication is Assassin’s Creed in December. Directed by Justin Kurzel (Macbeth) and starring Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard, the film has a good pedigree. Furthermore, the franchise has an intriguing premise and plenty of opportunity to tell a contained story without requiring the greater world setup that Warcraft did. Whether or not the film succeeds, it is only a matter of time until the right team, with an understanding of both films and video games, gets behind the right franchise to produce the adaptation we have been waiting for. Until then, the unique style and presentation of video games will continue to seep into films, like Hardcore Henry, and fans of both mediums will patiently wait for the day we can watch Commander Shepard’s signature dance moves on the big screen.