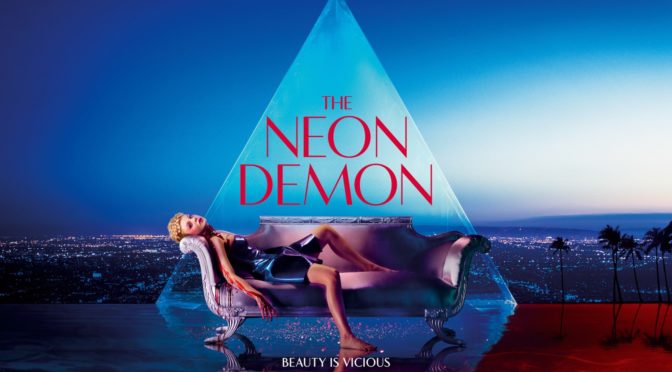

Coming off the less than stellar reaction to Only God Forgives, Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive) returns with The Neon Demon, a film about a young woman, Jesse (Elle Fanning; Super 8), who moves to Los Angeles to become a model. She says she isn’t smart, has no real skills, but knows she’s pretty and she can make money off of pretty. The topic makes an interesting change of pace for Refn who has centered most of his films around hard men and criminal underworlds. What is fascinating is how little his portrayal of these seemingly disparate settings varies. He shoots the hyper-competitive field of modeling in the same way he normally frames opposing gangsters. The players are as vicious as they are unscrupulous and when Jesse quickly becomes the “it” girl leaping over established models who have been working towards the same goals for years, we see that these two environments are more similar than we had imagined.

Regular composer, Cliff Martinez, returns with another stellar soundtrack. He again uses a variety of electronic music to set the tone of the film. His pulsing beats provide an effective contrast to Refn’s slow camera movements. They add much needed energy and tension to what could otherwise become a lethargic film. Martinez has also expanded the emotional range of his music. His rhythms immediately create atmospheres of dread, adrenaline, or heightened reality, depending on the scene. Tracks like “Are We Having A Party” quickly set the tone of events to come. His score combined with Refn’s images make the film an audiovisual treat.

Refn exploits the world of high fashion for his own visual sensibilities. The signature cinematography from Only God Forgives is further intensified here. The images look ripped out of an avant-garde art gallery with stark backgrounds and characters drenched in high contrast lighting. He adds depth to these images by examining the potentially abusive nature of their creation. These young women, Jesse is underage but is told by her agent to say she is older, are at the whim of older men who Refn rightfully indicts as predatory. Other models repeat that the quickest way to get ahead is often to give in to the sexual desires of these gatekeepers. The only flaw to the director’s analysis of these men is that he doesn’t acknowledge that he too may be in a similar relationship with his actresses. Fortunately, none of the sumptuous imagery, even when it becomes explicit, feels like it is shot with a leery eye.

The threat of violence and its attachment to beauty is present throughout the film. The opening shot tracks in slowly on a motionless Jesse, made-up and wearing a shining dress, with a stream of blood dripping from her neck setting an ominous tone for the story that follows. Characters rarely use dialogue with a natural back and forth. Instead, they spout sentences with long pauses between responses, creating a dream-like quality. This serves to make otherwise standard interactions appear foreign and forces critical analysis of what we accept as normal and why, similar to the way David Lynch often directs his actors.

The unintended effect of this delayed cadence is that it also distances the viewer from the story. While the plot is much simpler than his previous film, the characters again aren’t empathetic because they don’t seem human. Jesse begins the film with some understandable naivete but then quickly assumes the same cold demeanor of her peers, making even the audience vessel unrelatable. This reduces the impact of the film’s climax. While the images are still unsettling, it’s the literal actions that shock more than their implications. Without developing strong investment in the characters, The Neon Demon is a series of visually arresting, but emotionally lacking, images with a superb electronic score.

3/5 stars.