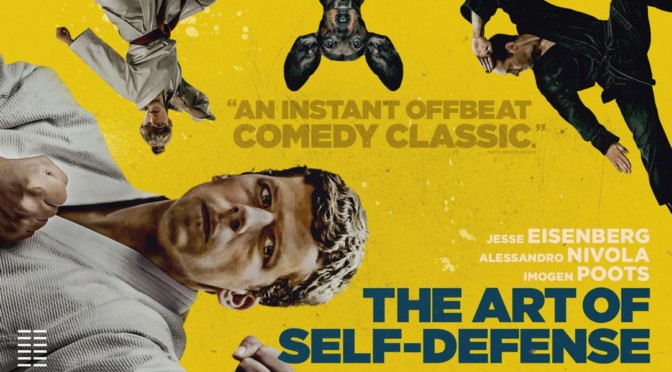

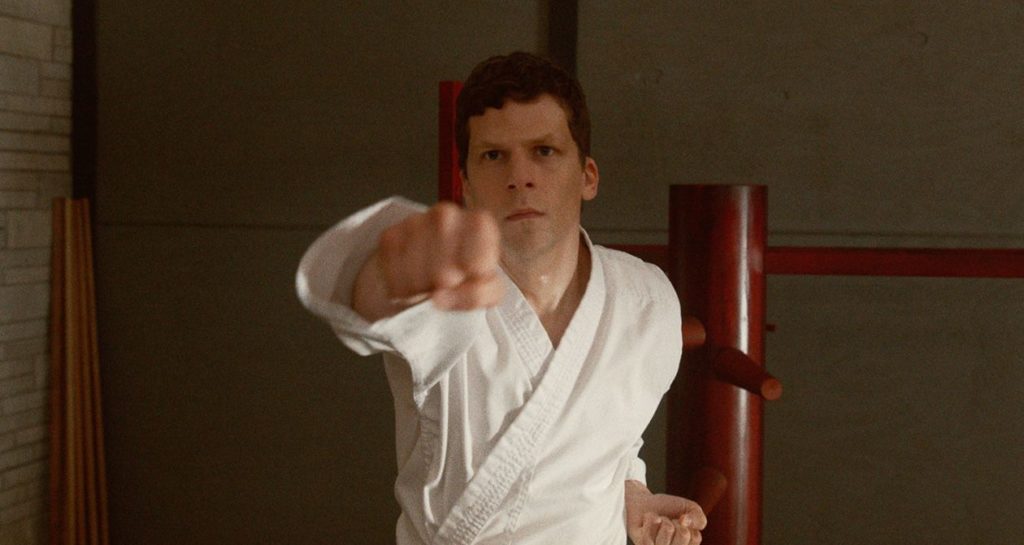

Casey (Jesse Eisenberg; The Social Network) is an awkward, lonely accountant that lives his life without much companionship other than his Dachshund. On a quick trip to the grocery store to buy dog food one night, he is brutally assaulted by a gang of motorcycle-riding muggers and is left in the hospital for days. Now petrified of the world, he stumbles upon a karate class and is wowed by their physicality. He quickly joins and devotes himself to the teachings of his Sensei (Alessandro Nivola; Face/Off).

After initially claiming he joined for “health and fitness reasons”, Casey confesses “I’m afraid of other men”. He feels weak, powerless, and is hyper-aware of his lack of masculinity. Characters, Casey included, comment on how he has a feminine name. Karate becomes his way to change his identity and “become the thing he fears”. To make this possible, Sensei tells him to change every aspect of his personality. He starts listening to metal and alters other superficial aspects of his life to “commit” to his goal.

Director Riley Stearns (Faults) uses this transformation to critique cultural norms. Sensei’s advice is narrow, ridiculous, and often results in aberrant behavior as Casey moves beyond assertive to aggressive responses. Eisenberg delivers the controlled performance that is perfect for the material. When he becomes “Masculine Casey” he still carries the awkward mannerisms of his original self, but overcompensates with the aggressive language and body movements of someone forcing themselves to do something they are completely uncomfortable with.

Stearns is able to balance this critique with frequent moments of levity. The film can be depressing as Casey struggles with his confidence when he is insulted and taken advantage of by others, but it also points out how society’s expectations of men shouldn’t be considered normal. This is especially true when they try to explain themselves. Sensei speaks of his dojo’s traditions with complete seriousness and in the same breath talks about replacement fees for karate belts.

This balance is held together by an incredibly tight script. The film’s plot has several reveals that will leave viewers shocked but still follow a logical progression. Stearns weaves in subtle hints at where the story is headed throughout the film. Every single aspect of the narrative, from the rules on the dojo walls to Casey’s perceived femininity is essential to the plot and Stearns deserves enormous praise for creating a script that is at once dense with details and completely devoid of filler.

The Art of Self-Defense is essentially the anti-Fight Club. Fight Club centered on a similarly weak main character that changes into something else under the influence of a stereotypically masculine figure. The tragedy of that film, while flawlessly executed by director David Fincher, is that the majority of viewers not only missed the point of the film, they completely misinterpreted it. Many left believing the film was in favor of Tyler Durden and his anarchic beliefs because of Fincher’s slick style and Brad Pitt’s charismatic performance, despite the opposite being the case. Stearns leaves no room for this same misinterpretation. Violence is depicted as savage and unnecessary rather than cathartic and the “manly” characters are shown for their own absurdity and used for humor or just as pitiful beings. The Art of Self-Defense is a morbidly funny, tightly crafted, skewering of the hypocrisy of traditional masculinity and an strong entry into Stearns’s growing filmography.

4/5 stars.