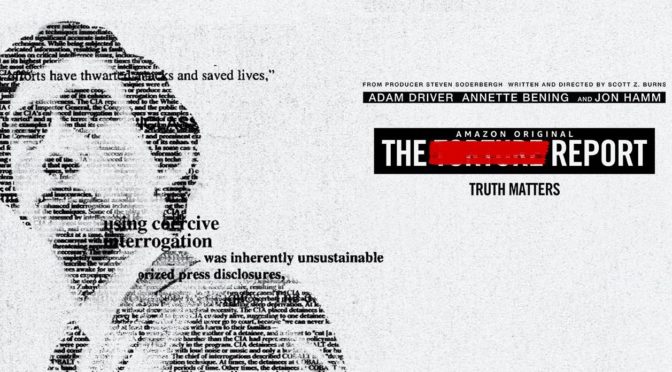

The Report is a procedural about the writing of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture led by Daniel Jones (Adam Driver; Paterson), a member of Senator Dianne Feinstein’s (Annette Bening; The Kids Are All Right) staff. Directed and written by Scott Z. Burns, the writer of Contagion, the film uses a similarly methodical pace and approach to the material. Like Steven Soderbergh, who is also a producer on this film, Burns invests time in the minutiae of bureaucracy and is able to depict the gargantuan effort required to review millions of documents, create a 6,700 page report, and get it released without exhausting the audience’s patience.

Driver is perfect for the role of Jones. He has a cool demeanor and the commitment of a focused, tireless worker. He comments on how he used to be in a relationship, but the writing of the report didn’t allow enough time to maintain it. In his interactions with the CIA and senate staff, Driver emphasizes Jones’s persistence and later his emotional investment. As he faces more scrutiny, Driver’s responses become faster and more forceful and make it obvious the opposition’s arguments are fallacious. His immediate retorts show the depth of his knowledge and the passion he has for publishing the truth.

The depiction of torture is likely to cause some controversy. Burns does not sugarcoat any of the grisly aspects of how prisoners were treated. The chief antagonists are the self-proclaimed interrogation experts that developed the enhanced interrogation techniques (EIT). These two come from military backgrounds but are revealed to have never participated in any type of interrogation. They act as contractors, instructing others to undress, beat, sleep deprive, and waterboard their detainees until they talk. Alongside them are several CIA staff that support their methods. The prevailing notion is to extract info and prevent future attacks “by any means necessary”. Burns shows how the fear created by 9/11 and the desire for some sense of justice morph into cruelty and how unchecked support of the CIA led to unspeakable acts, made easier by the fact that the detainees were foreigners.

The film places significant blame on those that cover up their mistakes. The CIA is shown going to great lengths to sell enhanced interrogation to the public. They have agents do interviews claiming that EIT directly led to the killing of Bin Laden, using their major success to justify their wrongdoings despite the fact that internal reviews showed that the techniques did not produce any unique information. As sick as the torture is, the degree to which an organization will protect its reputation above any moral responsibilty is perhaps the most loathsome aspect of the story.

Burns’s ultimate goal is not just an indictment of torture, but a reaffirmation of what are United States government is supposed to represent. Committing torture is a terrible mistake, but hiding its use from the public is an act of deception. Using rousing speeches from Benning and real life clips from Senator John McCain, Burns reinforces the importance of accountability, admitting to mistakes, and improving over time. He as created a detailed film about a difficult part of American history that is as diligent and through as its protagonist.

4/5 stars.