The world of animation has becoming increasingly similar. Despite growing options with new technologies, most companies opt for computer generated 3D animation. As beautiful as these renderings can be, the lack of diversity is disheartening with Japan remaining as the main producer of feature length 2D animation. The Girl Without Hands is a welcome visual change, featuring a singular hand-painted 2D art style animated entirely by its director Sébastien Laudenbach. The film is an adaptation of the fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm. It is the story of a miller that mistakenly trades his daughter for wealth in a deal with the devil and follows her as she faces the fallout of his decision.

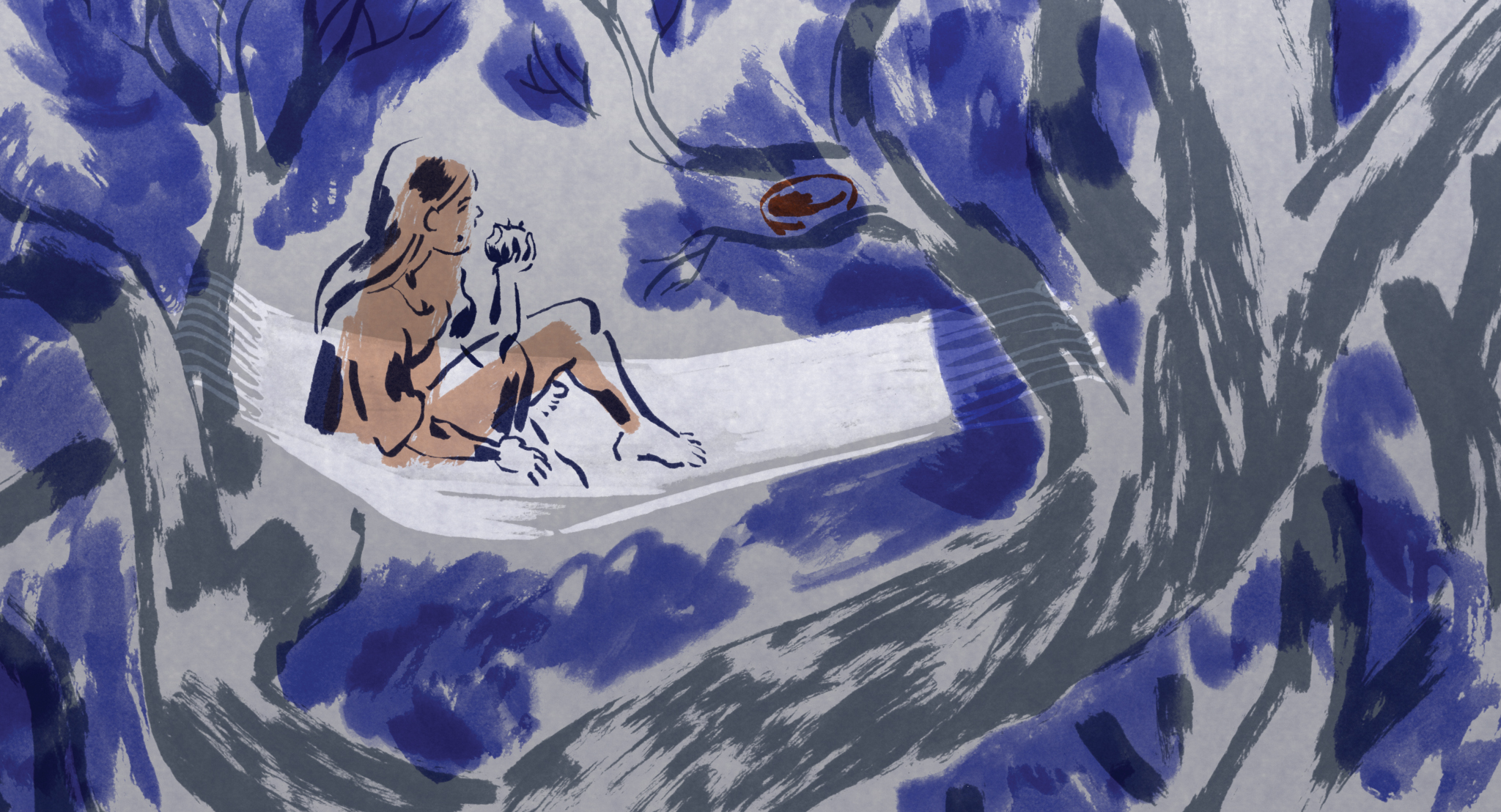

Laudenbach’s art is the film’s most distinctive quality. He uses a minimalist, yet expressive style. The images are less like drawings and more like etchings. Each frame has a colored background with objects shaded in rather than explicitly outlined in a sort of spartan impressionism. The background colors are textured and often have a gentle gradient that sets the mood for each scene and the brush strokes are painted on similar to watercolors. The film animates by having these strokes pulsate and is particularly effective when depicting water or wind. The rippling colors perfectly encapsulate the energy and movement of nature. Laudenbach also has a unique method of showing the emotional state of the characters. Because they are so minimally sketched, he can paint a broad stroke of color over them and even as the character moves, this mark remains, showing their lasting presence and the unchanging state of their mind. His indirect approach to his images gives the film its unmistakable storybook quality.

If only the screenplay wasn’t also of storybook quality. The original fable is short and the film, while running only 76 minutes, still feels overlong. The material hasn’t changed significantly in adapting it for the screen so there isn’t enough content to justify the runtime and what is present is too simplistic. As gorgeous as it is, the film is clearly an excuse to show of Laudenbach’s beautiful images. Several scenes are elongated just to feature the artwork. The story, with its fairytale roots, never produces any emotional response. This is a fantasy world that is too detached from our reality to create a connection. There is supposed to be a moral lesson about admonishing the pursuit of wealth, but it is delivered using blunt platitudes that are as generic as they are groan-inducing. A character says to the girl’s father, “You are rich. How could you be at peace?”. These aren’t new or creatively presented insights. This might be a trait that stems from the source material, but even so that doesn’t mean it translates well in a film. The few original flourishes added to the story are scenes that show the director’s gross and unnecessary fetish with genitals that has no place in something that was originally meant for children. Laudenbach’s artwork and animation are uniquely expressive and minimalist, but the story they present would have been better suited to a picture book, not a feature length film.

2/5 stars.