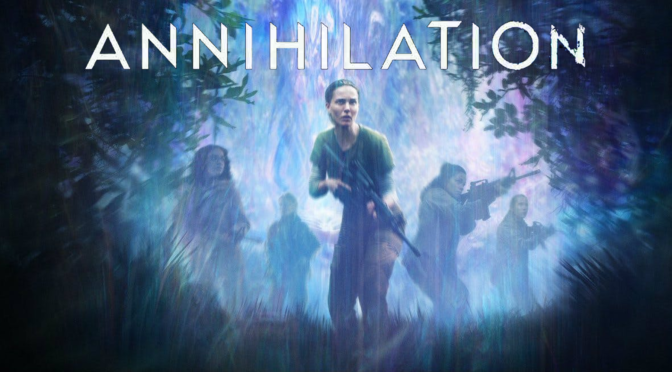

Writer-director Alex Garland (Ex Machina) has carved out a niche for himself. With his newest film, he reconfirms his interest in smart science fiction. Making drastic changes to the best-selling novel by Jeff VanderMeer, the film follows Lena (Natalie Portman; Black Swan), a biologist and military veteran, who is taken to a government facility hiding a secret. A crashed meteorite has created a transformation known as Area X, or as the Shimmer for its glowing borders, and no one has ever returned from inside. She, along with four other women, are assigned to enter the uncharted zone and find its source before Area X expands to the rest of the country.

Garland strikes a unique balance between heady sci-fi and monster movie. Like a Tarkovsky film, the pacing is generally slow. In most cases, unnecessarily slow. There are repeated flashbacks that drag on without adding depth to Lena’s backstory, but there is also a blend of horror and action. The women of expedition team wield assault rifles and know how to use them with the script providing ample opportunities to do so. As they explore the wilderness, Garland follows the trappings of horror with near-death encounters and increasing paranoia that create sustained tension. Someone reports that there are two main theories why teams never return: something beyond the Shimmer kills them or they go crazy and kill themselves. Garland never provides an answer with each subsequent event seemingly flipping the odds in the other direction and thereby leaving the audience in suspense.

There is constant fear of the unknown within Area X, but also an unexpected beauty. Garland makes the environment lethal with dangerous, malformed creatures lurking around every corner. His methods are effective because the setting isn’t entirely alien. The flora and fauna are perversions of a natural setting and everything glows with a pallid, ethereal luminescence. Things feel close enough to normal that the differences become stark and disturbing. Animals resemble their traditional forms but are distorted in size, shape, or features. Flowers and fungi-like growths bloom throughout the landscape, but their initial beauty is complicated. The unnaturally colorful plants undulate as if they are feeding off the wildlife, almost carnivorously, and add to the mistrust surrounding every new encounter.

In VanderMeer’s original book, the title referred to a specific event, but Garland has a much higher concept in mind. In a revealing conversation, a character corrects Lena about the differences between self-destruction and suicide and exposes the heart of the film. Whether it’s the wildlife of Area X, cancer, or relationships, Garland is interested in the transformative, damaging, and regenerative consequences of self-destructive actions, but he isn’t explicit with his conclusions. The film’s ending is abstract and ambiguous to the point that it will frustrate viewers who tolerated the film’s slow rhythm in hopes of an explanation. The sequence itself is well executed and creates a genuine sense of wonder, but it will be divisive. Films don’t need clear or easy interpretations, they’re often better in ambiguity, but Annihilation leaves ideas open for discussion without providing enough resolution to make the long journey there worthwhile. Garland renders a deadly, corrupted environment with noble, high concept goals, but the needlessly slow pacing requires more from the narrative than it can provide.

3/5 stars.