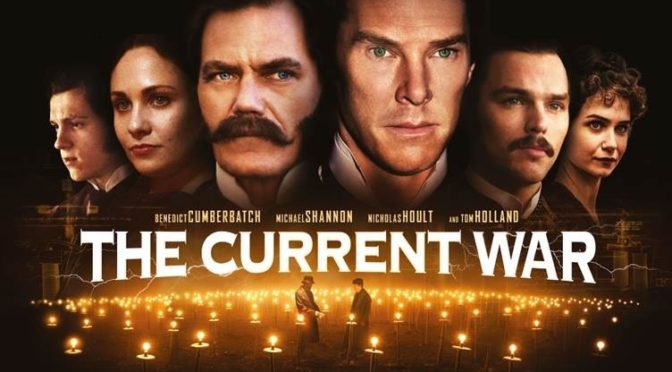

After premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2017 to negative reviews, The Current War: Director’s Cut has been overhauled with new scenes and editing that form an exciting historical rivalry. Thomas Edison (Benedict Cumberbatch; The Imitation Game) seeks to power the country with his patented direct current and uses his fame to spread the technology. His rival, George Westinghouse (Michael Shannon; Take Shelter), favors using alternating current for the distance it can travel and the two become locked in a battle to electrify the nation.

Despite its appearances, The Current War is not a lethargic period piece. The film moves at a brisk pace and never lingers too long on a single moment, ironic considering one of Westinghouse’s earliest inventions was a braking system. The camera is also always on the move tracking characters, often at oblique angles, and there is an interesting use of repeated cut-ins, timed rhythmically during pivotal decision moments, to add weight to situations. Director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon (Me and Earl and the Dying Girl) never allows the period or its trappings to prevent the film from appealing to modern sensibilities.

In his portrayal of these pivotal historical figures, Gomez-Rejon is fairly kind. Cumberbatch, utilizing a slightly improved version of the annoyingly flat fake American accent from Doctor Strange, makes Edison a bit of an egotist, but not quite the ruthless businessman many accounts have described him as. He’s relentless in his pursuit and unwilling to conform to the ideas of others, but his moral digressions are shown as lapses in judgement caused by desperation rather than standard practice for his business. Even as he uses underhanded tactics to smear his opponent, he never becomes a villain.

Westinghouse, on the other side, is the practical industrialist. Shannon makes him seem like a no-nonsense proprietor who manages his affairs with integrity. Unlike Edison, he seems principled and focused on the work rather than its marketing. Where Edison will step into the spotlight, speak to reporters, and sign autographs, Westinghouse refrains from spectacle. In a crucial sales opportunity, he ignores any sort of demonstration and instead lets the buyers know his product is better and cheaper, hands them evidence, shakes their hands, and walks away. Shannon’s pragmatic gruffness and his laconic lines reveal Westinghouse to be the true lead of the movie, with a ethical code worth rooting for.

The film also features Nikola Tesla (Nicholas Hoult; About a Boy) in a minor role as a brilliant inventor that briefly works for Edison only to later develop a key technology for Westinghouse. His role in the real events may have been significant, but his limited screentime make him feel like an afterthought, used mostly for his now ubiquitous name recognition and for one particular line that winks directly at the audience.

The competition between Edison and Westinghouse becomes an exciting horse race. The men are shown as always being on the verge of winning the battle, but also precariously close to complete failure with media issues, personal problems, and financial worries constantly threatening to thwart their success. Their strategic moves, and their impulsive decisions, create an engaging chess match, even though the outcome of their rivalry is known. The Current War: Director’s Cut is an involving, bustling drama about two great titans of industry locked in a literal and figurative power game.

4/5 stars.