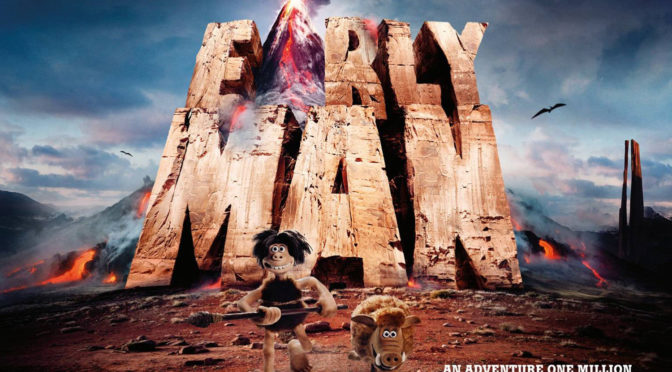

Directing his first film in over a decade, Nick Park (Wallace & Gromit) and the wonderful team at Aardman Animations (Chicken Run) have created another hilarious stop-motion romp. Set in the Stone Age, the story follows Dug (Eddie Redmayne; The Theory of Everything) and his fellow cavemen who are forced out of their valley by a Bronze Age nobleman named Lord Nooth (Tom Hiddleston; Thor). Desperate to get his homeland back, Dug bets Nooth that his tribe can beat Nooth’s all-star soccer team. If the cavemen win, they can return to their valley, but if they lose they will be forced to spend their lives working in Nooth’s bronze mines.

A cast of prominent British actors has the time of their lives doing the voicework. Redmayne as Dug is an eternal optimist whose springy voice implies he always has another idea up his sleeves if things don’t work out. His resilience is as charming as his naivete, but the real standout has to be Hiddleston. Lord Nooth gives him the chance to be the villain Loki (his character in the Marvel Cinematic Universe) never could be. He is deliciously evil, savoring every injustice he can create and every piece of bronze he can swindle. Yet, his ludicrous scheming is kept light by his blatant incompetence and his fear of how the Queen will react to his actions. He is the epitome of the likable, but bumbling villain, perfect for an audience to laugh at, but not with. Topping off the performances is a variety of vaguely European accents. Ricocheting between western European countries, the cast’s adopted speech only heightens the farcical plot and adds to the film’s absurd tone.

Early Man is filled to the brim with inventive humor. Unlike most animated films, Park doesn’t rely on desperate fart jokes to get a laugh out of his audience. He uses the Stone Age setting to create ridiculous situations with the peak being a gargantuan, man-eating mallard duck and then mines the culture clash of the cavemen entering the Bronze age. There are setups with characters using ancient technology for modern communication, particularly a running gag involving a messenger bird, that are priceless. As the soccer match ramps up there is also a surprising amount of sports related humor. Subtle digs at prominent real-world teams and a caricature of sports commentators are welcome additions that even non-soccer fans will enjoy. Aardman’s humor goes beyond single jokes. Each scene is packed with unexpected sight gags that make the film worth a second viewing. It has the rare combination of both quality and quantity of jokes that will keep audiences of all ages laughing.

The simple plot may be a slight disappointment to some. While Park takes advantage of the humor that the Stone Age brings, the film quickly and unexpectedly turns into a sports movie with an unusual backdrop. The beats leading up to the soccer match follow the expected tropes including a training montage, a struggle to perform, and a new member that motivates the team. It’s impossible to not wonder what zany situations the cavemen could have faced if Park had leaned further into the prehistoric setting (more man-eating mallards would have been appreciated), but there is plenty to love about the story that is present. Despite its familiarity, it’s the unique spin Park adds that prevents it from becoming cliché. Under his direction, and with the work of his stellar animation team, Early Man is a consistently hilarious, beautifully crafted, and uniquely Aardman take on the sports movie.

4/5 stars.